Renee Baker Took Flight in New Directions at VCFA

Renee Baker was already forging new paths in music by the time she came to VCFA. She had established herself as a strong musical force, with her Chicago Modern Orchestra Project. She went to the school seeking credentials to aid her in the cut-throat world of art music. And she found that. But she also found an environment that let her explore all of her wildest creative impulses—and an unexpected partnership that sent her off in a whole new direction.

“The teaching part of my life was long over,” Renee says. “I was 55 when I applied to this school. I don’t think they knew why I wanted to come here.” But Renee knew exactly why. “What you are purchasing is the affiliation, the ability to attach the identity of the business to your name. This is the be-all and end-all of what colleges are. When you go into it with that in mind, you go in trying to grab everything you can. It’s like the blue light special at Kmart. I’m taking my buggy and I’m grabbing as much as I can as fast as I can. That’s how I approached it.”

And she did grab everything. Renee was hoping to learn more about nontraditional notation, and more avant-garde methods of composition. “Everything I submitted was , but I knew when I came that I wanted to spend some time studying nontraditional notation. And that’s where I dove in feet-first, head-first, butt-first. Because I felt that was a safe environment to explore it in.”

She made friendships with her mentors that have lasted to this day. She credits her first mentor, Jonathan Bailey Holland, with setting the tone of the program for her. That first semester, she was working with a unique system of graphic scores—gorgeous, vividly painted works that guide performers through a piece under her guidance. These paintings don’t look anything like traditional music scores. She came in that first semester with 16 paintings, 19×30 each, as her piece to be performed. Jonathan found the unique approach interesting, and was eager to hear the results. Renee knew it was unorthodox.

“I said ‘I promise I won’t leave you with egg on your face. I know what I’m doing.’ And it was a huge hit and it kinda set the pace. After that, I felt free.” She cites Jonathan’s openness to exploration as a huge part of the program for her—perhaps even the most important part of the student/mentor relationship. Renee’s directness and clarity of vision are legendary, and Jonathan trusted that and let it flourish. She says, “VCFA meets the student wherever they are in their compositional life, and gives each student wings.”

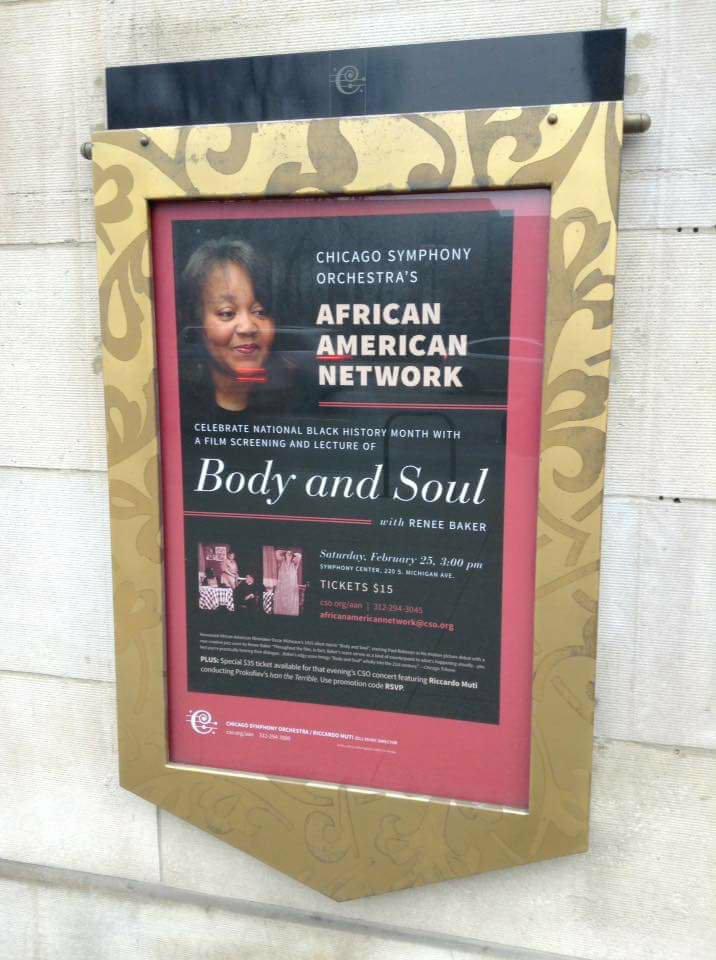

Renee was tearing through new ideas at a speed all her own, staying up late and poring over rare scores and books in the library. But then a faculty member sought her out with a proposal she wasn’t expecting. Don DiNicola wanted her to score Body and Soul, a 1925 “race film” by Oscar Micheaux. She’d actually had producers pitch her the film before, and nothing had come of it. Don’s sincerity won her over, but she had a condition. She wasn’t going to try her hand at snippets or scenes. She was going to score the entire feature-length film. It was unheard of in the program and wildly ambitious for a six-month workload. But Don dove right in with her.

Renee’s scoring is bold work. Rather than rely on themes for individual characters, like you might see in a John Williams score, her music cuts straight to the heart of a scene’s emotional struggle. She goes past the surface-level interactions and into each character’s inner turmoil. “Don was really responsible for helping my ideas to crystallize. He’d send me pieces (of the film) in small batches and I’d send something back. It was that partnership that really helped formulate the truly abstract nature of how I think, and distill it into film scoring. That really is my nature. Don’t let the housewife disguise fool you.”

“This man taught me so much about how to look at film, how to look at what’s going on in the background, things that normal viewers don’t even see. He had me studying what was on the walls, the shoes they had on. The tables, and chairs, and then at the end of that process he said, ‘So you know you’re a film composer, right?’ I said, ‘Yes, I do.’ He said, ‘You’re also a filmmaker. I listened to your comments, and everything you said, and you’re a filmmaker.’ I said, ‘Nah I don’t wanna make film.’ But now, of course I’ve got probably 20 experimental films in rotation. Because Don took the lid off and gave me permission. You can open something here. I came in really wanting to look at extremely contemporary classical music, and develop my vocabulary for graphic scores, and then meandered over the line, crossed the lane into the film scoring.”

At the time, Baker was working on an opera, Sunyata—another point of synchronicity with Don DiNicola. “I told him, ‘it’s about the time period after you’re pronounced dead, to the time that you’re actually gone.’ He said, ‘oh, you’re talking about the Bardos!’ Next thing I knew, Don gave me this fabulous translation of the Tibetan book of the dead, the source material my opera was based on.”

She was already talking to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago about producing the opera. But when they learned about her Body and Soul re-score, they jumped at the chance to premiere that, as well. It was a hit. And it sparked a massive jumping off point for Renee, who never does anything in half-measures.

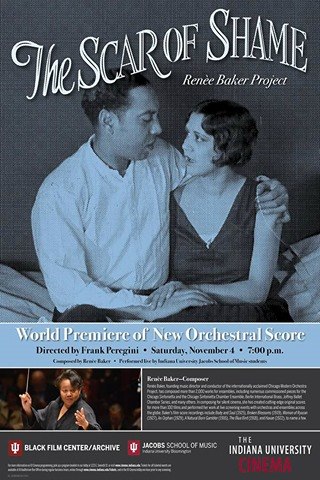

“When I’m interested in something, I exhaust it before I move on. At this point now, I’ve probably scored over 150 silent films. I’ve actually developed 14 film festivals. I developed themes crossing all sorts of boundaries. Ethnic boundaries, geographical boundaries, and matched films that you normally would not see together. I took the first one to Indiana University last year. They did a four-film festival of my work. And that precipitated another invitation. I just got back from an almost two-week residency at Indiana. They wanted a score to The Scar of Shame, a 1927 silent, using the orchestra from the Jacob School of Music, interaction with people in the jazz department, lecturing on film and sound design to film classes and taking in my own experimental series into their Black Experimentalist classrooms. It was amazing. They said, ‘We need you to touch all the areas.’ I talked to composition students, film students, jazz students, orchestra students.”

She also puts on screenings locally with the Chicago Modern Orchestra Project

“It’s from an ugly period in our history, but didn’t Charlottesville just happen? It was such a challenge for me, and I put it in the can. Then Charlottesville happened, and when the ACLU called me, I said ‘I have just the vehicle.’ This is information. We need to see it. Especially in light of the fact that it was the first feature-length film shown in the White House. And Woodrow Wilson thought it was a masterpiece, with the KKK saving the white people from us. The score brings it to today.”

The film scoring has blown up in a big way for Renee. From her screenings in Chicago, to residencies at universities, to screening at film festivals across the world, it’s taken her already-booming career to new heights. She credits the combination of her self-starter attitude and VCFA’s openness.

“What impressed me was a comment Jonathan Bailey Holland made. He said, ‘This is your program.’ I am 2,000 percent a self-starter. I left there with nothing I wanted to explore left unexplored. Go knowing what you want to get out of a master’s-level program. For me, I wanted validation of concepts, of research, of exploring. I wanted it validated for a program of this time. This program left me open. There were no closed doors.”

You can stream and download tracks from the Chicago Modern Orchestra Project at their Bandcamp page here.

Renee’s website is here, and includes a store where you can check out her recent film work.Running sports | Footwear