Three Penny Records: Connection, Composition, Commitment

Three Penny Records is a cooperative record label started by three alumnx of the MFA in Music Composition at Vermont College of Fine Arts: Jenny Davis (’18), Vanessa Littrell (’19), and Tiffany Pfeiffer Carr (’19). Recognizing the power of music to make change, they aim to improve the music business for independent artists… and change the world for the better. A statement from their website reads, in part:

As creators, we aspire to reflect inclusion and acceptance toward all people, to cultivate awareness of our role as stewards on this planet, and recognize the power of music to do that. Now is a vital time to inspire a change of hearts and minds through music.

Jenny, Vanessa, and Tiffany graciously agreed to spend some time answering questions about Three Penny Records, reflecting on the process of creating a record label, and talking about their larger goals.

Can you each tell me a little bit about yourselves?

Vanessa : I live in Snohomish, WA, just north of Seattle. When asked what I do I always laugh a little, because I bounce through so many different roles. At any given moment I am a teacher, director, playwright, vocalist, dancer, painter, graphic artist, percussionist, actress, or pianist. Currently, I teach visual arts at a local high school. Is that what I do? Sometimes! My musical background includes teaching private music lessons for twenty years, directing three musicals, writing and producing three albums, and performing as a vocalist/guitarist/pianist in multiple projects. At VCFA, my focus was more on the musical theater side of things. However, while I was there I also presented a choral piece centered around my son’s bipolar episodes, created an eight-minute vocal rant curated by the devil and several wind instruments, wrote a wind overture for the musical “The Bridge” and collaborated on multiple rock, folk, spoken word and street songs for the singer-songwriter nights.

Vanessa : I live in Snohomish, WA, just north of Seattle. When asked what I do I always laugh a little, because I bounce through so many different roles. At any given moment I am a teacher, director, playwright, vocalist, dancer, painter, graphic artist, percussionist, actress, or pianist. Currently, I teach visual arts at a local high school. Is that what I do? Sometimes! My musical background includes teaching private music lessons for twenty years, directing three musicals, writing and producing three albums, and performing as a vocalist/guitarist/pianist in multiple projects. At VCFA, my focus was more on the musical theater side of things. However, while I was there I also presented a choral piece centered around my son’s bipolar episodes, created an eight-minute vocal rant curated by the devil and several wind instruments, wrote a wind overture for the musical “The Bridge” and collaborated on multiple rock, folk, spoken word and street songs for the singer-songwriter nights.

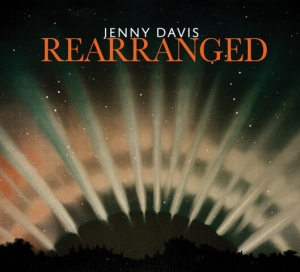

Jenny: A Seattle native, my love of music began early—at 9, I was performing in a traveling children’s choir. In high school, I sang in bands and studied with renowned vocal instructor Maestro David Kyle. My undergraduate was at Cornish College of the Arts (Seattle) in Jazz studies. The music business has provided many roles for me: international performer, composer, recording artist, band leader, booking agent, vocal coach and producer. After parenting and operating/owning a successful airplane business, I eventually lived my dream of dedicating two full years to music composition, earning my MFA in 2018 at VCFA. The freedom of jazz with the celebration of authentic expression drew me in as a composer. Taking my ideas onto the bandstand, I began to hire horn sections to play my arrangements and original material. This led to my collaboration with VCFA colleagues and the release of my latest album of original music, inspired by my human rights activism. The album, Rearranged, is our first release at Three Penny Records. It’s amazing to see our label on the charts with Blue Note and other established labels!

Jenny: A Seattle native, my love of music began early—at 9, I was performing in a traveling children’s choir. In high school, I sang in bands and studied with renowned vocal instructor Maestro David Kyle. My undergraduate was at Cornish College of the Arts (Seattle) in Jazz studies. The music business has provided many roles for me: international performer, composer, recording artist, band leader, booking agent, vocal coach and producer. After parenting and operating/owning a successful airplane business, I eventually lived my dream of dedicating two full years to music composition, earning my MFA in 2018 at VCFA. The freedom of jazz with the celebration of authentic expression drew me in as a composer. Taking my ideas onto the bandstand, I began to hire horn sections to play my arrangements and original material. This led to my collaboration with VCFA colleagues and the release of my latest album of original music, inspired by my human rights activism. The album, Rearranged, is our first release at Three Penny Records. It’s amazing to see our label on the charts with Blue Note and other established labels!

Tiffany: I’ve lived in Vermont for the last twelve years, in rural small towns and for the last two, in Burlington with my now husband. I moved here from Brooklyn, NY, so I was more in need of dirt roads and moose sightings than “city” bustle, though I love being in Burlington and the arts scene here. I run a private music studio where I teach voice, piano and composition, and spent many years playing gigs with my band and solo all over Vermont, as well as back in NYC. A double-booking led to me sitting in with a local jazz band in early 2010, and since then I’ve also been performing and collaborating as a jazz vocalist, both domestically and internationally. I’ve released two albums, an original EP recorded back in Brooklyn, and an EP of jazz standards. I’m originally from the Midwest, studied voice and magazine journalism at Drake University, and moved to San Francisco out of college, where I was editorial director of an underground arts culture magazine. At VCFA, I focused on writing for various instrumentations to go along with my songwriting persona, and learned to trust that the many parts I hear in my head are worth writing down! I’m currently working on arranging those songs for performance and recording as soon as that’s possible.

Tiffany: I’ve lived in Vermont for the last twelve years, in rural small towns and for the last two, in Burlington with my now husband. I moved here from Brooklyn, NY, so I was more in need of dirt roads and moose sightings than “city” bustle, though I love being in Burlington and the arts scene here. I run a private music studio where I teach voice, piano and composition, and spent many years playing gigs with my band and solo all over Vermont, as well as back in NYC. A double-booking led to me sitting in with a local jazz band in early 2010, and since then I’ve also been performing and collaborating as a jazz vocalist, both domestically and internationally. I’ve released two albums, an original EP recorded back in Brooklyn, and an EP of jazz standards. I’m originally from the Midwest, studied voice and magazine journalism at Drake University, and moved to San Francisco out of college, where I was editorial director of an underground arts culture magazine. At VCFA, I focused on writing for various instrumentations to go along with my songwriting persona, and learned to trust that the many parts I hear in my head are worth writing down! I’m currently working on arranging those songs for performance and recording as soon as that’s possible.

I assume the name, Three Penny Records, is inspired by our beloved Three Penny Taproom, a favorite gathering place in Montpelier, VT for the Music Composition program.

When we first discussed a name, we were trying to find something that represented the three of us as women musicians and composers who strive to push boundaries, both in our music and in the world. Of course, VCFA is what connected us, so something that represented that time in our lives made sense. Three Penny came up, because of the memories at the taproom, because of the three—and then we looked into the history of the Threepenny Opera as capitalist critique, as well as the threepence coin of the UK, this formerly low-value, but now sought after artifact, with the faces of women leaders (Queens Elizabeth I, Victoria, Anne and Elizabeth II) on the front—and the name really seemed to fit from several different angles.

How did you decide to create your own record label?

It was on the afternoon we came back to Tiffany’s house in Burlington after the Music Composition Alumnx Residency ended in August 2019. We were all exhausted and inspired, as is usual after residency, and Vanessa and Jenny had some time before they needed to catch their red-eye flight back to Seattle. Jenny was talking about her upcoming album and we were discussing everything we’d learned from Frank Oteri and Trudy Chan at the residency as far as the business end of album promotion, and just how much there is to do. Then we all kind of thought aloud, what if we had help? We’ve all put out albums on our own before and know how overwhelming it can be, and how easy it is to miss important elements. We talked about how the record industry continues to change, and how individual artists are empowered to do it all themselves, but that it’s just too much. All of us teach and wear multiple hats as working musicians, and we realized an opportunity was there to come together and create something to help each other, as well as other like-minded musician/composers, to get the support and exposure we need to thrive.

Your website describes Three Penny Records as “Womxn Curated Music for the Future.” And you have a mission of fostering “support, accessibility and advocacy for independent creatives through a cooperative record label.” What need(s) does Three Penny Records fulfill that you aren’t seeing addressed elsewhere in the industry?

First of all, as “womxn” curated, we mean that we are cisgender, LGBTQ/BIPOC allies and feminist women who use womxn to distinguish ourselves from a patriarchal capitalist system, and that we strive to support music that pushes that system to change. We consider this the “music of the future”, because although the world is changing now, it has much further to go to create gender, racial, economic, and environmental equality among all beings. This is what drives us to make music, and we feel like our mission, along with our cooperative model, distinguishes us from most other record labels out there. Rather than operate as an exclusive club, we hope to inspire others to push for social and environmental justice through their music, so that as artists we are not perpetuating a system that ultimately holds us back. This mission is the driving force behind the musicians we choose to invite into our cooperative, and because of that, all genres are equally relevant. The continuity is the drive to create fundamental societal change.

You are all composers and singers, but with very distinct creative voices. Can you talk about the commonalities among the three of you—musically or otherwise—your shared values, and what it is that connects you and drives this successful partnership?

Ever since Vanessa and Tiffany were paired as roommates their first residency, that connection was instant, and soon enough the uncanny commonalities between Vanessa and Jenny became apparent as well. The three of us spent a lot of time together, or in various pairings amidst each other, and what surfaced was an ease of communication and a relatable appreciation of the spiritual realm. We all believe in the power of coincidence, of being present in the moment, and this knowing makes for easy translation of our thoughts and intuitions to each other. Although we don’t all write in the same style, we each have an urge to be progressive in the world and to create music that reflects that urgency. We also have a deep trust and investment in each other’s success, and our past trials and tribulations go into a shared pool of knowledge that we can all draw from. Our diversity of experience just adds to this well we can access both separately and together.

You began creating Three Penny Records before COVID-19, with two of you located in the Pacific Northwest and one in Vermont. How does distance affect your collaboration?

We were already meeting regularly on Skype and Zoom, so it’s really been the same since COVID. It’s been invaluable to have our meetings and each other as we’ve gone through the various stages of quarantine and as we’ve all been adapting to teaching and maintaining our musical presence online. The distance is great really, because we have a connection to both the West and East Coasts—we bracket the U.S. and can keep a broader perspective. When travel becomes easier we will definitely have in person meetings and events both in Seattle and Burlington.

Do you have plans to expand your label to include more artists?

Absolutely, but we are not in a rush. Right now we are promoting Jenny’s jazz album Rearranged, and Phoenix by Sugar Addikt, Vanessa’s EDM project with her son Bowman. We are writing bylaws and ironing out the legalities of becoming a business and a cooperative. Tiffany hopes to record in the semi-near future, so that may be our third release, but whatever organically comes up and feels right we will definitely consider.

Any news you’d like to share?

We’re pretty excited about the charting success of Jenny’s album, Rearranged. Three Penny has been listed alongside labels like Blue Note and Mack Avenue, so that’s a fantastic way to start off. And Phoenix, mastered by VCFA’s own Ravi Krishnaswami, has just been released in the past couple of weeks, so we’re looking forward to seeing where that will go. Find us on social media to keep tabs on our releases and upcoming events—we can’t wait to continue to share with the VCFA community and beyond.

Can you each tell me a little bit about yourselves?

Can you each tell me a little bit about yourselves?

Approximately 2 1/2 years ago, this newly-minted 60-year-old student stood on stage at the Vermont College of Fine Arts to receive his Masters Degree in Music Composition. It was a time of reflection – this was probably the last formal education I would receive. After all, I WAS 60 years old, at a time in life when retirement is considered the norm, not going back to school.

Approximately 2 1/2 years ago, this newly-minted 60-year-old student stood on stage at the Vermont College of Fine Arts to receive his Masters Degree in Music Composition. It was a time of reflection – this was probably the last formal education I would receive. After all, I WAS 60 years old, at a time in life when retirement is considered the norm, not going back to school.